While working in the area of dealing with the past within the region of former Yugoslavia for several years already, and despite the fact that we were focused on the “recent past”, that is, the wars of the 1990s, we would often encounter taboos, silence and injustice dating far more back in the past. We have discovered in this way, among other things, all those things that we don’t know regarding what had happened with our former German neighbours after the WWII. This has induced us to conduct a small research, and in front of you lays the report on our journey trough Vojvodina in November 2010. We hope that we will find a way and the capacity to do even more than this.

The 60-year silence

Report of the journey through Vojvodina

CNA has been working on dealing with the past for several years now – we believe that we have no future unless we look back and question ourselves, the others and the past itself. Also, with regards to that, we believe we must point out the injustice done to those who are “no longer present” among us, such as Bosniaks in Republika Srpska, Serbs in Sarajevo, Albanians in Belgrade, etc. Even though our work is focused on the wars of the 1990s, the stories often go back as far as the WWII, as well as the period before and after it.

There is an ongoing discussion within the Serbian society on who was good and who bad, if the Chetniks are the same as the Partisans, which are better and which worse, what are the Chetniks and what are Ravnogorci, and similar. Discussion is being conducted about various issues, but there is one group one keeps silent about or whispers, which were (especially back then) a part of the society –very little has been said in public. We are talking about the Germans who had lived in the former Yugoslavia. Or, as they are popularly referred to, the “Podunavske Švabe” or the “Folksdeutschers”.1

Many will say: “Well, what is there to say?”, “The Germans are to blame for the war”, “Those are just some there…”, “Considering how they were, they ended up just fine”, “as if we don’t have enough of our own worries”, “all are victims and all are guilty”, “that was a long time ago, the future is ahead of us”, etc.

Throughout November we had travelled around Vojvodina and were conducting a research in order to obtain as much accurate information as possible about them in particular, about those of whom people remain silent – about the Germans from these areas who survived the war and the period after it, about their destinies and descendants, the injustice done to them, about the silence and the shame, wishing to make the injustice at least a bit more visible.

The basic information with which we embarked on our research

Between 510.000 and 540.000 thousands of Germans were living within the territory of the former Yugoslavia prior to the WWII, accurate information is unavailable. Today there is officially 3.901 of them, out of which 3.154 are in Vojvodina. Around 67.000 civilian Germans perished after the WWII. According to the AVNOJ decision brought on the 21st November 1944, all the property of Yugoslav citizens of German origin was to be expropriated, and the Germans were collectively denounced as national enemies. Thus, they were not denied their citizenship, but rather their civil rights.2 From October 1944 the Danube Germans were interned into detention camps. By August 1945, all the villages in which the Danube Germans had lived were “cleansed”. Only those DGs who were married to persons of other nationality or those who had fought on the side of the Partisans were exempted from this.3

Since the end of October 1944 in Banat, and since mid-November 1944 in Bačka, until June 1945, the following occurred:

• 7.000 civilian DGs (including women, children and the elderly) were executed and murdered.4

• Deportation of the DGs to labour camps in the USSR. Around 2.000 persons died in them due to hunger and diseases, but were also murdered.

• Around 5.000 DG war prisoners were murdered.5

• Slavisation of children of the PGs: since 1946 thousands of children were deported into Yugoslav homes for abandoned children for re-education and “slavisation”. Some of them still have not found, or still don’t know, their origins.6

• Around 167.000 DG civilians (out of 195.000 DGs that had remained in Yugoslavia) were imprisoned in camps.7 In the period between 1944 and 1948, around 48.500 DGs, out of which 35.000 in Vojvodina, died as a result of executions, maltreatment, malnutrition, heavy physical labour and disease.8

There were around 100 camps within the former Yugoslavia, most of them were in Vojvodina. They were not all set up and run at the same time, and also, the DGs were not only interned into special buildings, but the whole villages were being used as camps. Those villages were guarded by the Partisans or the police.

The most notorious camps were those in Knićanin (Banat, out of 33.000 DGs interned between October 1945 and March 1948, almost 11.000 died), Gakovo (Bačka, 8.500 persons died from March 1945 to January 1948), Kruševlje (Bačka, 3.000 persons died from March 1945 until January 1948), in Sremska Mitrovica (Srem, 2.000 persons from 1945-1947), in Molin (Banat, 3.000 persons from September 1945 until April 1947) and in Bački Jarak (7.000 DGs perished from December 1944-1946).9

With this information we embarked on a tour of Sremska Mitrovica, Sombor, Gakovo, Odžaci, Apatin and Subotica.

A few words about our visits and tours

Sremska Mitrovica

This was the first meeting and the tour of the place where the Danube Germans were killed. We met Jovica Stević. He used to be the secretary of the local football club “Radnički” which is located in the part of Sremska Mitrovica which had been mostly inhabited by Germans. He had found out by accident that there is a mass grave right next to the stadium, in which people dying in the camp in immediate vicinity of it were buried (the former silk factory, known amongst the Germans as the scaffold “Svilara”). The walls of the building of that camp and the place of the mass grave in its immediate vicinity can still be seen today. The camp was fenced with a barbwire, the windows were walled up, except for the tiny holes.

There is another mass grave on the Catholic cemetery, and from recently also a monument to the Germans killed from 1944-1948 who are, according to Jovica Stević, estimated to number around 2.000. The monument was erected on the site of the mass grave, due to an initiative by Jovica Stević, and in collaboration with the Germans from Germany and Austria. By the way, out of 11.000 residents of Sremska Mitrovica in 1944, 3.000 were Germans. Today, according to the official census, there is 200 of them, but unofficially they are around 1.000.

It was moving to see those places, a havoc with a few erected grave stones. At the site of the mass grave, one can see a few tombstones. It had often occurred that the Danube Germans were being made to dig out the graves themselves, and those who had recognized the murdered persons would mark the place of the burial place with a bottle or a piece of wood, so that the relatives would know where the victim was buried, as was the case with little Helga whose spot was latter marked with a small monument (see the picture at the beginning of the text).

While reading about the Svilara camp, we encountered the words of Katarina Gaislinger, an inmate: “One day in January we were sent to unload the tow boats on the Sava River. This hard work, which lasted 14 days, had to be done with bare feet, as it was expressly ordered… This winter specifically, we had to stand outside every morning in a line. ‘Woe’ to the sick who would not come out immediately. The guards, armed with wooden sticks, would force the helpless ones towards the exit with hits and kicks. Some would manage to get outside only by crawling.10 In December 1945, during a visit of a man in a civilian suit and with obvious political power, Traudi Miller-Vlosak heard him asking the camp commander while walking along a line of beds: “How much longer until they all die? I am surprised that so many are still alive.”11

Sombor, Gakovo, Kruševlje

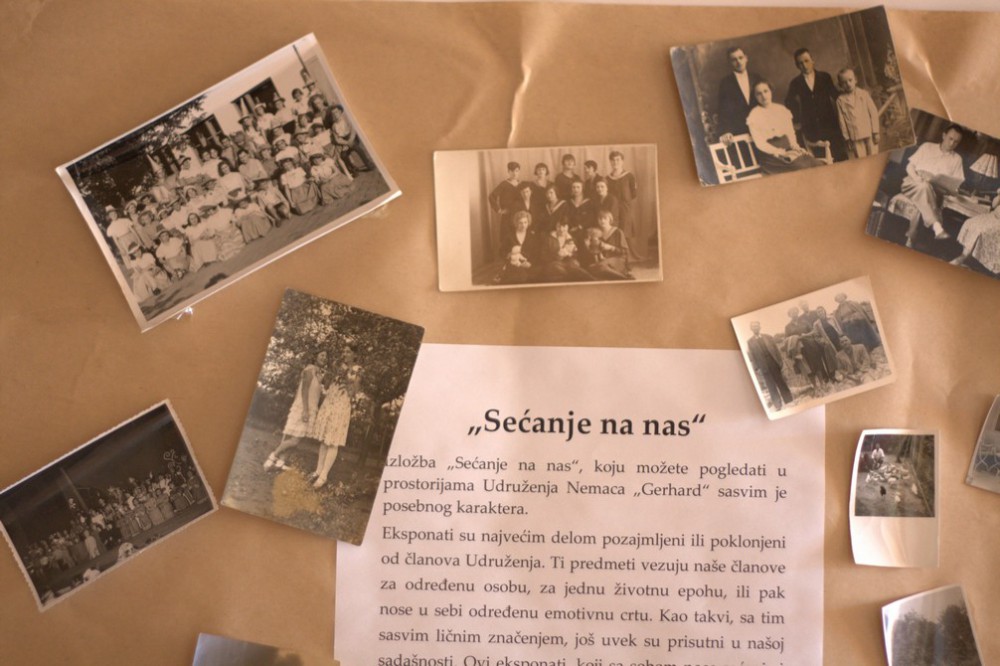

In Sombor, we have visited the “House of Reconciliation” and the “Gerhard” association. We spoke about the past and current position of the Danube Germans, about the camps, about the recording of the memories, about the fear and shame of talking about the past.

Sombor is the place where Danube Germans were collected into, a sort of a collection point, from where they were sent off to camps (children and the elderly most commonly to the Gakovo camp), to work on farms and agricultural land. The place where now stand a kindergarten and a bus stop is still referred to as “the camp”. Not many residents of Sombor, especially those of younger generations, know why that place is called particularly that. The camp consisted of eight barracks, in the middle of the yard was a truck without wheels, “in it were put priests and teachers, educated people, with their hair completely cut off. Every once in a while they would be taken outside, to the place for the roll-call. They were being assembled in a circle; they had to kneel, and then the guards would dance a traditional dance “kolo” around them and spit on their heads”.12

Gakovo, the same as Kruševlje, is located near the Hungarian border. The first camp prisoners were Apatin residents, around 6.000 of them. In 1931, Gakovo had numbered 2 692 residents among which 2 370 were Germans, while towards the end of 1945, 17.000 inmates were compressed into the emptied houses (22.000 according to some accounts). During the first 10 months 4.500 of them had died or were killed.

A monument was erected on the site of the mass grave in Gakovo in 2004. The monument was set up by the German national council and the “Gerhard association”, and the set-up itself was accompanied by extensive negotiations with the local authorities. There were objections to the monument but it was eventually erected, but with two empty plates on which it will be possible to write the text which is completely in line with the events (this that currently exists is a kind of a compromise). So far, it hasn’t been desecrated (except once with 4C). There used to be a fence between the graveyard and the mass grave with the monument, but it was removed on the initiative of a woman who was present at an occasion when people from Germany came to visit. According to the people who told us about this, that woman, after having a conversation with a visitor from Germany, said that the pain for the dead is equal and there should not be a fence between people who mourn their own.

The Kruševlje camp is located relatively close to Gakovo; however, in the event of rain, it is difficult to reach it as there is no real road. This camp was notorious for the cruelty of the guards and the public executions that were being ordered by the commanders.

The attempts to escape from these two camps were common during the period of their existence as the Hungarian border is near. People often escaped to Germany through Hungary, and those journeys would last for weeks and even months.

Odžaci

We have spoken to the pastor Jacob Pfeifer who shared with us a small part of his personal story – his parents were in a camp as well (Knićani). They found it difficult afterwards to talk about their experiences from the camp. This has been kept silent before the children. According to his information, 183 persons were killed in a field near Odžaci (182 actually, as one had survived) on the 23rd of November 1944, and they are known by their names and surnames. Several Danube Germans were set aside in order to dig a big grave for their compatriots, and then they were killed as well. There is a story of this place being “cursed” as nothing grows there. A monument will be erected on this site in June 2011.

Apatin

Boris Mašić is the President of the Apatin society “Adam Berenc”. Apatin was the place where the German colonists, coming to Vojvodina via the Danube, were arriving and from there were deployed further. Prior to the WWII there were about 14.000 Germans in Apatin, comprising around 98% of the population. Further, according to his words, the German pre-WWII population was divided to approximately to one half being the “green” ones (supporters of the national-socialists) and the other half “black” (slightly older population, more connected to the Church and against Hitler’s politics). The most outstanding in his opposition to the national-socialists was the priest Adam Berenc, who was tolerated by the Hungarians under who’s occupation was Apatin, with only occasional “harassment”. After collapse of Nazism, the “green” Germans mostly left for Germany together with the German army (7.000 of them), and the majority of those who stayed were against the Nazis (around 7.500 of them). Out of these that had remained, around 4.500 got killed. There was around 1.500 Germans in Apatin after the WWII. Officially 156 Germans reside here today (between 200-300 unofficially).

Boris Mašić has a personal story in his family, related to the suffering of the Germans. On the 14th of December 1944, his grandfather was taken to Sombor, along with 70 other Germans, where he was tortured and subsequently killed, and his grandmother was in the Gakovo camp and had somehow managed to survive. All the property of his family was confiscated, except the two houses in which they live. It is well known who killed his father, and that man is still walking free around Sombor. A commemorative plate has been placed on the building in which he was murdered together with other Germans, however not on its outer wall which is facing the street, but on the inside one in the so called “einfort”(corridor). Mašić is trying to preserve the cultural heritage of the Germans (he has a big library with books that he has been rescuing, mostly from ruined churches, out of which the oldest dates back to the year 1600). According to him, we will have a difficulty finding people in Apatin who will be ready to speak about the sufferings of the Germans because of the fear that still widely exists.

A personal story: Jacob

Jacob has always had a distinctively German identity, but never in public – only within the circle of the people he knows well, so he would start speaking in German or would listen to German music. He was born in Apatin in 1932. After the war, according to his words, many people in Apatin mostly feared the Red Army soldiers, but Jacob’s experience was different – they were hanging out together and he started smoking with them. But when the communists came, everything changed: their property was confiscated, his father ended up on a cargo train headed for Russia, together with the other Germans, for Kharkov; they picked him up on Christmas 1944. Jacob never saw him again. Mum was taken to Sombor to the camp with together with other women. After some time she started working in the houses in Sombor and eventually, after more than a year, she escaped and had returned to Apatin. Initially, she had hidden for a while and later she just registered herself in the municipality. His aunt and uncle ended up in the Gakovo camp, the uncle died and the aunt had managed to escape to Germany, to Ulm. Later, around ’53, she was joined in Ulm by Jacob’s mother and sister.

Jacob says that it is known what was happening in Apatin during those years, however, they do not talk about that when they gather within the framework of the” Adam Berenc” society. It is mostly spoken in German. He is very happy when he hears German songs, it makes him happy. In the end of the conversation he said “you have not heard anything from me, my name will not be showing up anywhere, right?”

Subotica

We have gained an insight in what was happening to the Germans in Subotica after the WWII from Rudolph Weiss. There exists a mass grave here as well. On 2nd of November 1944, in a single day, 300 Germans were killed and, together with Hungarians and anti-communists (over 1 000 persons) were buried in mass grave. There exists a monument on that spot today, and the mass grave is appropriately marked by the Municipality of Subotica, as a result of the initiative of the families of the murdered and there buried. A commemoration takes place there every year, on the 2nd of November. We have also heard a lot of moving stories, such as the terrible stories of the raping of young girls (Eva Bischof, 9) and women. In Srpska Crnja, in November 1944, approximately 70 women committed suicide in a single night because the previous evening the drummer had announced a mass rape.

For the end…

No one was ever persecuted for what had been happening to the Germans. Some of the perpetrators are still alive and free. There is an impression that there was no organized system of covering-up of what had been going on inside of the camps even at the time of their operation, but on the other hand, that was never spoken of, as is not talked about even today (Ivan Ivanji wrote a feuilleton in continuations in the NIN weekly dealing with the position of the Danube Germans after the WWII, in which conversations with several members of the local communist authorities of that time, who were in all possible ways publicly denouncing the crimes, were published. Look from the number 2677 and further). The locations of the mass graves are known, although the number of those murdered is not precise, and the archives hold the information of the sufferings and the ways of suffering, but all that is still not available to the public.

There is still today a strong sense of fear, and even shame, among the people (especially among the survived Germans) to speak of what they have survived, or their parents, grandparents… Those who no longer live in Vojvodina are probably more ready for that. It seems that this issue is hard to approach as it stood deeply buried for over 60 years, some felt ashamed, some feared (when they asked an elderly lady to day something about her experience, she said “I can’t, I will loose my pension”, and before she used to be afraid she would loose her salary. Some felt ashamed of what had happened to them – “Should my grandson find out I was raped?”). Apart from that, considering the fact that the Danube Germans needed to hide their identity and not express it publicly, it is no wander that this dimension of shame, that makes the story even more difficult and complicated, exists.

Visits from Germany, primarily of the family members of those who died in Vojvodina, but also of the representatives of societies and officials from the FR Germany which became frequent since 2000, as well as the erection of monuments, are in some ways influencing the recognition of injustice and are making the victims more visible, but they also decrease the tension towards the Germans among the local population (it is primarily meant the colonists13) as they get to understand that they are not coming to take away their houses and land, but rather to visit the places of birth and death of their own.

It is important that the Republic of Serbia has founded a commission for determining the facts about the crimes of the period between 1944-1948 with Srđan Cvetković from the Institute for Contemporary History (that is, the Secret Graves Commission of those murdered after 12th of September 1944), and that this body acts under the auspices of the Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Serbia.14 However, this commission also works on the finding of the body of Draža Mihajlović, an issue which a significant part of the Serbian society started ridiculing (“the Homen case”15).

Apart from that, another important decision has been brought by the Parliament of Vojvodina – a decision has been made that there is no collective guilt that refers to the German population of Vojvodina.16

As we found out from Jacob Pfeifer, the initiation of the case before the Court in Sombor for rehabilitation of the murdered Germans around Odžaci, is of special importance, and that case currently sits at the Higher Court.

The demanding claim is to pronounce innocent those two had died , but that is still a “controversial” matter as it concerns, as the judge put is, a greater number of people (!?). If we are not mistaken, it is about 40 people in question.

Anyways, all those we spoke to during these visits and meetings have expressed their readiness to support us in raising the issue of destinies of the Germans after the WWII. They think it necessary and about time, as the witnesses soon won’t be alive.

For the end, as professor Zoran Žiletić says in the preface of the book “A People on the Danube” by Nenad Stefanović: “One inevitably wanders what has been happening to us since 1944 up to now, when we have accepted that not only an eradication of the whole nation is done, but that we is remain silent about it for more than half a century.”

Nedžad Horozović, Helena Rill & Jessica Žic

December 2010

* * *

1 We will be using the term ‘Danube Germans’ as the term ‘Schwab’ was used derogatively throughout all these years.

2 The Yugoslav law of the 31st July 1946 determines: the expropriation concerns all Germans, apart from those who fought for the Partisans, or were active in the liberation movement, who were assimilated prior to the war, then those who were married to the South Slovenes or to another minority, nationality that was not an enemy of the Partisans. (Bundesministerium für Vertriebene, Flüchtlinge, und Kriegsgeschädigte 2004:103E).

3 Donaudeutsche Landsmannschaft in Rheinland-Pfalz e.V. 2003:74.

4 Arbeitskreis Dokumentation 1994: 16.

5 Arbeitskreis Dokumentation 1994:16.

6 Donaudeutsche Landsmannschaft in Rheinland-Pfalz e.V. 2003:75.

7 Arbeitskreis Dokumentation 1994:4.

8 Arbeitskreis Dokumentation 1994:17.

9 Arbeitskreis Dokumentation 1994:17.

10 Working group for documentation 2004:150 (Genocide against the German minority in Yugoslavia 1944-1948).

11 Ibid.

12 Nenad Stefanović, Jedan svet na Dunavu , p. 72.

13 The colonists came to Vojvodina after the adoption of the Law on the Agrarian Reform and Colonization (brought in August 1945) from different regions: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Banija, Lika, Kordun, Montenegro, Dalmatia, Sandžak, Serbia, Macedonia, Slovenia and Kosovo. Around 250 000 people arrived in a short time. Organized colonization was conducted in the end of 1945 and during 1946, but the immigration continued until 1948. The colonists had inhabited 114 places in Vojvodina. According to that law, the new owners have been granted 668 412 ha of land.

14 More about this commission at: http://www.komisija1944.mpravde.gov.rs.

15 Homen is the name of the state secretary exposed in media regarding the case of Draža Mihajlović’s grave search (reference by N.V.)

16 The Parliament of the AP Vojvodina has adopted a Resolution on the unrecognizing of the collective guilt on the 28th of February 2003.