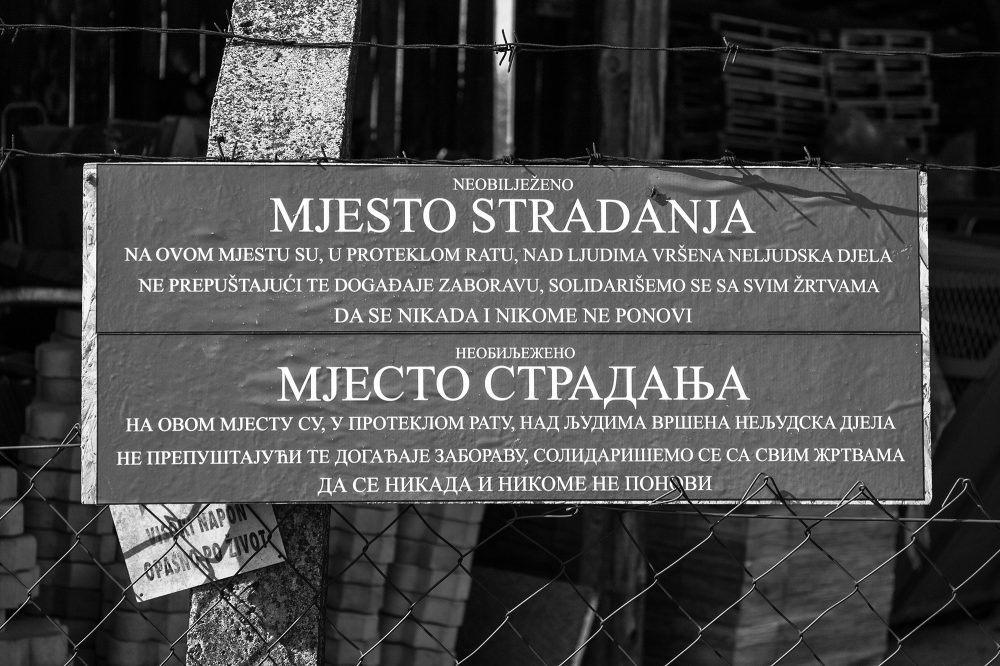

The team for marking unmarked sites of suffering continued its mission of marking forgotten and unwanted locations of suffering for the fourth time. This time, we had two new additions to the team. Amer, Čedo and Dalmir were joined by new team member Tamara and freelance journalist Ajdin Kamber who did a story on our activities for Deutsche Welle.

We started our activities in Sarajevo, in the crowded Hamdije Kreševljakovića Street, former Dobrovoljačka Street. The name of Dobrovoljačka Street is regionally recognised as a place of defence of Sarajevo and a place where the deal about the retreat from Sarajevo was broken. Images of commemorations for victims have long been overshadowed by scenes of confrontation between veterans of ARBiH and families of the victims under heavy police protection. Although the events in Dobrovoljačka are a contentious topic and there is still no court judgement, we conducted research and found that the indictment states that a crime was committed in Dobrovoljačka Street against disarmed and captured members of the JNA. Although the site was full of people waiting at the nearby trolleybus stop, our action went by unnoticed. It seems things are least noticeable in a crowd.

The next day, we intended to mark the Cultural Home in Pale, which in the summer of 1992 served as a place of detention for some 600 persons, mostly Bosniaks. Researching available data on the exact location of the building, we found that the former Cultural Home building in Pale had been renamed the Cultural Centre. However, when we arrived, attached the stickers and took photographs, we attracted the attention of employees who came out to ask who we were and what we wanted there. They tried to persuade us that we had the wrong location and that during the war their building was the home of TV SRNA. We left the site in disbelief and went to check with local contacts whether we had the right building. They confirmed that this was the only building in Pale that served as a cultural home. Later, after we posted about this on Facebook, we received the same complaints, but we were convinced this was the kind of denial we often face in local communities. This conviction held until we were contacted by a man who explained that in the 1970s the former Cultural Home was turned into a gym and a new building was constructed which now serves as the Cultural Centre. He also explained the context of war events in Pale, confirming that the former Cultural Home was used as a detention facility. As soon as we found this out, we took down our post and decided to mark the correct location as soon as possible. We had made a mistake, but without it, we wouldn’t have been able to have a public discussion on our page that ultimately led us to this new information.

The greenhouse in Rogatica served as a site of detention of Bosniaks through the 1992-1995 war. The prisoners were subjected to harsh conditions, abuse and murder. The crimes committed at this site have been established in a number of international and domestic court judgements. We found the location with the help of our friends from Rogatica, but when we were marking it, we noticed we were being watched by people on the greenhouse premises, who then proceeded to follow us in their car as we left. Taking a few turns around the centre and down the small streets of down-town Rogatica, we managed to lose them, but when we turned onto the main road, we noticed a police car following us. As we were leaving the town, we were stopped by two police cars with 6 police officers and 2 inspectors. The police procedure started on the road, they took our documents and started asking us all sorts of questions, even for some banal information such as height and years of university, which we interpreted as a type of psychological pressure. Without returning our documents, they said they were not arresting us, but that we should come down to the police station with them for an informative talk. There, we were met by the station chief with epaulettes adorned with 4 stars. He was young and evidently well-educated. He used an official and authoritative tone, but was polite in communication with us. We explained our activity and mission and managed to soften the rigid police procedure. After warning us that we were putting ourselves in danger and disturbing public peace and order, they asked us whether we were planning to mark anything else in Rogatica, and since we were not, they let us go with a warning. Still, the station chief’s last sentence tells us that there is support for what we are doing. He wished us luck and that we “continue with the mission”. We thanked him for treating us properly and left Rogatica, continuing on to Bijeljina and the Batković agricultural cooperative.

The encounter with the police shook us and upped our adrenaline levels, but it also demonstrated once again how difficult and complex it is to deal with sites of suffering that local communities would rather forget.

Due to unforeseen events in Rogatica, we reached Batković only at sundown. Without time for reconnaissance of the location, we attached the sticker to the front fence, took photographs, and as the guard looked on curiously and shots fired by hunters echoed in the distance, we quickly left the site.

We spent the night in Brčko, in Hotel Posavina, a location that was a site of suffering in the spring of 1992. We chose the hotel on purpose because we planned to mark it, but through communication with our hosts, war veterans from all three sides, and at their insistence, we decided against it. The decision not to mark the hotel was definitely reinforced by the strange situation of a hotel employee following us around and watching everything we were doing. The day wore on and we still had other locations to mark with our hosts in Brčko.

The JNA barracks in the centre of Brčko had seen much in the war years, as had the whole of Brčko, but the spirit of animosity and war is not apparent in the city at first glance; life is more visible. The barracks we were planning to mark are now home to various institutions of the District: courts, schools and a large parking lot, which is perhaps the best way to re-purpose a barracks. As we had agreed with our hosts, we did not attach stickers this time, but instead had a mobile board with the stickers already attached that we set up and photographed. After the barracks, we marked the buildings of the primary school in the village of Boće and construction material warehouses in Gornji Zovik that used to be controlled by members of the HVO and ARBiH. Unfortunately, although we had planned for it, we did not manage to mark another site of suffering that had been controlled by ARBiH.

Our next stop was in Šamac where our hosts were VRS veterans and where we planned to mark the buildings of the warehouse and stadium in Crkvina. In Šamac we also met with representatives of local government to present our initiative and received their support, in principle, for our activities. After visiting the memorial in Šamac and learning about the context of the war in this town, we arrived at the site of suffering in Ckrvina where Croats and Bosniaks had been detained and where 16 persons were killed on 8 May. We marked it, photographed it and, saying goodbye to our hosts, we continued on south.

In Zenica, we marked the site of the Music School. The cellars of the school building were used as a detention facility for Serb and Croat civilians and captured HVO soldiers. The marking proceeded without problems, and as we were leaving, we saw a few people gather to see what had happened. Later, through the media and web portals (more than 15 portals published the news) we found out the police had been called. News that a site of suffering had been marked in Zenica went around the country and brought welcome media attention to our activities.

In Visoko, we marked the site of the former Ahmet Fetahagić barracks where Serbs from Visoko had been detained during the war. The building where they were held used to belong to a Franciscan monastery before the Second World War, but was nationalised by SFRY and became a JNA barracks. In 2006, it was returned to the Franciscans. It now houses the Franciscan secondary school. An impressive building with a dark past, as we found out when we met with the Franciscan monks from the neighbouring monastery who told us about the people who had been detained there during 1992 and the testimonies they heard about what they had been through.

After Visoko and the barracks, our next location was the railway station in Podlugovi (immortalised in the hit song by Zdravko Čolić), which is still unmarked even though it is located in a community whose majority is from the same ethnic group as the victims from this location. The basement of the station was used by the VRS as a detention facility for Bosniaks and Croats from Ilijaš. As we were marking the building, a traffic police officer, who had been doing controls across the street, noticed us. With the experience from Rogatica still fresh in our minds, we were flooded with adrenaline in anticipation of police processing, but he called over his colleague and it turned out the colleague was a prison camp survivor who had been held in one of the detention facilities in Ilijaš. This time, we marked 10 unmarked sites of suffering. Even though this was the most complex and exhausting trip on our mission, it gave us hope for change in the future. We are extremely grateful for the support of our hosts in the field who are working to change attitudes towards taboo sites of suffering in their local communities and change things for the better.

Following the field activities, we uploaded the information and photographs of the sites of suffering to Facebook and Twitter and promoted our activities on these social networks.

Dalmir Mišković