Political and social contexts in which we work

Bosnia and Hercegovina: Not Great, Not Terrible

They are rare and extraordinary, those books that describe processes from the recent or more remote past and that by asking obvious though never considered questions describe in such plastic detail the present and foreshadow the possible future of a society. Max Bergholz manages to do this in his brilliant book Violence as a Generative Force that examines the violence in the small town of Kulen-Vakuf during the Second World War.

Bergholz asks a number of questions unfettered by time and place, the first of which is, of course, why did the violence happen? Not how, though reconstructing the course of events is key for any attempt to answer the question. As the historian Yuval Noah Harari observes, the question of why something happened just as it did is the central question of history as an academic discipline. Because, any attempt to answer it will unmistakably lead us, according to Harari, to the realisation that at some fork in the road of history, our forebears went one way and not the other. Years later, it is hard for us to explain why they took that path, while we clearly see a host of other options, which were perhaps invisible to our ancestors, that they could have taken, but didn’t. This liberation from historical determinism would lead contemporary humans to an awareness of their own responsibility for the choices society will make.

Experience of Violence

Bergholz develops Harari’s thesis by researching the events in a small area over a brief period. In answering the question of why violence happened in Kulen-Vakuf, Bergholz reveals the complexity of processes in a community that found itself in a vortex of violence, or rather, that was sucked into the violence. Here we see the relationship of central authorities to lower levels of government, local actors who promote violence, but also those who suppress it, we see the points when violence prevails and when it does not, we follow along as the spiral of violence, once set in motion, turns victims into perpetrators of (preventive or vengeful) violence… Later, all of this complexity is reduced through managed remembering (and forgetting) to an oversimplified us (victims, innocents, victors) and them (criminals, culprits, the defeated). Bergholz also deals with the issue of the extent and manner in which an experience of violence shapes the identity of a community.

Reading Bergholz, you feel like you have before you an excellent analysis of what happened in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the period between the elections (autumn 2018) and negotiations on constituting the government (autumn 2019). Bosnian-Herzegovinian society is predominantly marked by the experience of violence from the 1990s and memories of that violence. Scratch the surface of any topic, be it elections, politics, mass emigration, sports or culture, and you will find narratives, fears and memories that derive from the experience of violence, which again generates new violence.

This violence, though as a rule no longer physical, is present in society at all levels, and we can identify concrete examples of political violence, structural violence, cultural violence, environmental violence, etc. In contrast to the previous period, no attempt is made to disguise this new violence into some acceptable form, instead it is explained by the simple maxim: Better that we (outvote, discriminate, etc.) them, then they us. In the words of a local twitter warrior: You wanted democracy, well, democracy is when we outvote you because we can.

The elections fully laid bare the functioning of political violence. The call to vote in order to elect Željko Komšić (DF) as the Croat member of the Presidency was not packaged into any sort of story about a civic BiH, but simply presented as a mode of preventive violence to stop the election of Dragan Čović (HDZ BiH) to that position. The call, directed predominantly to Bosniaks, demonstrated how fear of concrete negative actions on the part of Dragan Čović and memories of experienced violence become a mobilising factor for a community. At the same time, Milorad Dodik (SNSD) mobilised his voters around a story about how his political opponents from SDS and PDP were mere traitors who have to be defeated. In his election campaigning, Dodik openly, at public rallies, threatened employees that they would be out of a job if they did not vote for his party.

Control of Memory

Bosnia and Herzegovina is an example of a country where the entire state apparatus at all levels is placed in the service of structural violence by the majority against the minority. Enjoying basic rights is possible only if you live in the appropriate part of the country where your people makes up the majority, and now legislation continues to support this model. For example, the Law on Civilian War Victims in RS that hinders or prevents Bosniaks and Croats from being given the status of civilian war victims. At the same time, new legislation in FBiH continue to prevent access to social rights by veterans and their families if they fought on the side of the so-called Autonomous Province of Western Bosnia.

Control of memory is certainly another area where majority violence against the minority is visible. In a war of memories, the memories of the other side are perceived as hostile, as something to be eliminated from the media, school textbooks, public discourse, etc. In Republika Srpska, two new commissions have been set up to investigate the victimisation of Serbs in Sarajevo and the events in Srebrenica from 1995. Without going into the final findings of the commissions and their work, it is clear that when Republika Srpska established these commissions, it was not out of a commitment to dialogue about a painful past and the legacy of the 1990s wars in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the region, or out of a desire to stop using this legacy to deepen conflicts and pose threats to the future. Statements given by the highest officials of Republika Srpska about the reasons for establishing the commissions and their aims in doing so, unfortunately, confirm this. The need to achieve recognition also for our victims (in this case Serb victims in Sarajevo and Srebrenica) and to call for the prosecution of war crimes committed against our people (in this case against Serbs in Sarajevo and Srebrenica) should not be abused in order to establish a counter narrative whose aim is to reinforce entrenched positions in the war of memories among the peoples in BiH, which is currently being waged. At the same time, the announcement by the president of Naša stranka Peđa Kojović that he is prepared to go and engage with people in Western Herzegovina and Republika Srpska in an effort to find a minimal common denominator about events from the 1990s was perceived by Bosniak politicians as absolute treason and the initiator was treated to a barrage of abuse.

Prosecuting war crimes was long a bright spot in the process of dealing with the past. Even today, BiH is more of an exception that the rule in global terms, when it comes to the number of prosecuted war crimes cases at domestic courts. Unfortunately, due to the sloppiness of the BiH Prosecutor’s Office, the politicisation of justice and attempts to merely keep up statistics, according to an OSCE report, the percentage of convictions in war crimes cases has dropped in the past five years from almost 90 to below 40 percent. In practice, this means that indictments are badly written and cases are poorly investigated, which only adds to the frustration of victims who are still prepared to testify. This ultimately makes room for political abuse of judgements where acquittals are celebrated without reference to parts of the judgement which acknowledge that crimes were committed, even though the accused were not found guilty of them.

In the past year, Bosnian-Herzegovinian society is as stuck as in the preceding years. Without having solved any of the contentious issues from previous years (changes to election legislation, disputes over NATO membership) new problems have now been to the agenda, partly through our own (in)action and partly due to global events, such as the refugee route that moved around 30,000 refugees through Bosnia and Herzegovina in one year.

As a rule, reactions to events in society are quick, fierce, mostly emotional, and everything is just as soon forgotten because the spotlights keep shifting. The best example is a case from Gornji Vakuf where a Bosniak reported that an unknown person or persons had scrawled offensive graffiti across his house and car. In a town that is today divided into the Croat and the Bosniak part, this caused a fair bit of concern, and oil was poured onto the fire from all sides. We’ll see who laughs last was said verbatim, but three days later the police found how the Bosniak who reported the graffiti had in fact scrawled them himself. A few apologies from those who were quick to cast the first stone and use the case to argue for or justify their claims about preventive violence as the only solution, a few deleted shameful tweets, hateful status updates and calls to mobilisation and that was that. The consequences in the form of a delivered dose of hatred, fear and hostility remain.

Who still remembers all the big talk about the introduction of reserve and auxiliary police forces in RS and the response from FBiH that theirs (police forces) will always be bigger? The murder of two police officers in Sarajevo who clashed with the car mafia has not been brought to light, and the murders of young Dženan Memić in Sarajevo and David Dragičević in Banja Luka remain unsolved. Protests that had lasted for months have quietened down in Sarajevo and were brutally suppressed in Banja Luka where for days the police hounded the citizens who assembled peacefully in the main square.

At the same time, all these events are not unequivocal or unidirectional in the sense that they offer only the prospect of more conflict. In the case of Gornji Vakuf, for instance, as soon as they heard the news, Croat neighbours came to the house with the graffiti, condemned the wrongdoing and pointed out that despite harsh wartime conflicts in Gornji Vakuf, there had been no incidents after the war. The fathers of the murdered young men, Muriz and Davor, lent their full support to each other and people from Sarajevo went to attend peaceful protests in Banja Luka, while people from Banja Luka came to Sarajevo. When the two police officers in Sarajevo were killed, their colleagues from Istočno Sarajevo gave full support to their families and participated in the investigation, saying that the same group had been responsible for attacks on police officers in Istočno Sarajevo.

There were events that demonstrated that we still have the creativity and will and knowledge to do good things. Sarajevo and Istočno Sarajevo hosted the European Youth Olympics Festival (EYOF), showing how we can cooperate in positive stories. This September, the first BiH Pride Parade was organised in Sarajevo under the slogan Ima izać’ [Coming out]. It has probably been years since a single event managed to polarise society to such an extent where the counter-demonstrations and public discussions brought to light a host of mechanisms revealing the inner-workings of our society: minorities have no rights, the majority gives them the rights that the majority wants them to have.

For example, the argument was used that the overwhelming majority of citizens opposed the parade, which should automatically mean that those in the minority should accept that they cannot have rights that the majority disagrees with, then there was talk of how the rights of the majority were being endangered and not those of the LGBT minority, which is another argument frequently heard when anyone mentions minority rights. There were also those saying that the minority should respect the feelings of the majority (another frequent argument) and the counter-rallies were organised to protect the traditional family defined so as to exclude not just LGBT people, but also heterosexual couples without children, widows, single parents, parents with special-needs children, etc.

The Pride Parade was organised primarily thanks to the courage, will and perseverance of a small group of activists and it was significant that they received support from the cantonal authorities under the leadership of Naša stranka and SDP. The first Pride Parade is important because it brought to light all the prejudice, discrimination and lack of understanding that we must continue to work on.

Brussels reported that in 2018, some 50,000 people from BiH emigrated to EU countries. Mass emigration is not a problem only for the economy, which is already feeling the effects of the departure of young professionals. It is a tremendous loss for BiH society, felt in all areas of life, including peacebuilding. It is difficult to make up for the already small number of people, especially in smaller local communities, who were willing to work on difficult topics such as confronting their own community with its painful past. On the other hand, BiH institutions do not have official data on how many people have emigrated, from where and to where, not to mention that nobody has seriously looked into the causes and consequences of this phenomenon.

All in all, Not Great, Not Terrible, as the chief engineer at the Chernobyl nuclear plant said in the popular series following the nuclear catastrophe.

Nedžad Novalić

Montenegro Context: And what have you got against Milo?

It has been another year that Montenegrin society has advanced at breakneck speed (much faster than the other societies in the region) towards the EU; it has continued to approximate what still represents or is at least being portrayed as a symbolic framework for upholding human rights and rule of law. At this incredible speed, soaring and flying, there are fewer and fewer chapters to open, negotiations to finish, laws to adopt and implement, problems to solve, conditions to meet. However, it seems that amidst all that speedy prosperity and welfare, we are left with a feeling of nausea, the dizzying climb has made our heads spin. Our brains and stomachs find it hard to adjust to the speedy driving down European highways, still under construction.

And what have you got against Milo? Many a citizen of Montenegro would ask after these introductory sentences. I’ve got nothing against Milo, nothing against DPS, either, and I’ve got nothing against Montenegro, if you really want me to follow that faulty logic, that is, official state policy. But allow me to explain what I am against.

Thieves of youth. Divisions and nationalism.

For too long, Montenegro has been hanging in the balance between, on the one hand, the impossibility of changing the government, which has become brazen in its omnipotence and increasingly arrogant, and, on the other, the opposition, which expresses its political futility and ineptness through the frustrations of a perennial loser. Citizens protest in alliance with the opposition calling for a change in government, failing to understand that the real struggle must be brought elsewhere – within the institutions of the system, with the aim of strengthening them and making them independent. I am against such an unchangeable state of affairs that has been going on since 1997, long enough to earn the label of “thief of youth” for a number of generations.

The political elites, among them outspoken antifascists, as well as their opponents, proudly point out and promote SFRY iconography, presenting today’s Montenegro as a continuation of Yugoslav anti-fascism and inter-ethnic harmony. Installing a monument to Josip Broz Tito in the centre of Podgorica is the most illustrative example of this new-old trend. And there would be nothing wrong if it weren’t for the constant neglect or deliberate oblivion to the growing gulf between, for instance, Montenegrins and Serbs. I am against increasing ethnic rifts in present-day Montenegro. Never more independent in our never deeper divisions.

On the other hand, much of the opposition, encouraged by an awakened and never more alert nationalism, seeks to minimise or completely abolish all the values we inherited from the secular and antifascist former large homeland, primarily the idea of a civic state and gender equality. As if following some second-rate script, ethnic motifs and blood and soil policies of the nineties keep cropping up like vampires, evidently never having been properly buried.

Of course, this is almost always seasoned with various interpretations, falsifications and understandings of the past, which in turn almost always become signposts for the future, i.e. directions for organising the state. There is neither will nor courage, and apparently nobody feels the need to deal with the not-so-bright present image of Montenegrin society. Instead, perspectives are focused far into an idealised past in search of legitimacy for present political action. Thus, for example, the Montenegrin parliament adopts a decision annulling the decisions of the Grand National Assembly from 1918 on accession with Serbia. I am against the trend of changing the past to change the future. “Misunderstanding its own past is at the heart of every nation”.

Army of the party. Criticism

I refuse to accept the lack of capacity at institutions, I am against incompetent civil servants. For years, high offices have been occupied by party soldiers (mostly lying in wait, but prepared to sit up and even jump when their master calls on them to do his bidding). They are, after all, better equipped than us to think and, of course, work better and more. I do not like seeing all those professionally humiliated by this, I don’t like seeing their offended civilities as they grin and bear it. This past year has been rich in scandals of university professors, ministers, etc. plagiarising papers and purchasing diplomas. All unpunished, of course.

I cannot accept the deep and still deepening social stratification. It almost always goes hand in hand with an incredible lack of constructive political and public dialogue about crucial issues. And the crucial issues are always there, inexhaustible and ever-present when we need to neglect our real problems. I admit I myself prefer talking about language than about low wages, about the church than about increasing emigration of young people from MNE, about this beautiful independent environmental country than about the cost of living being twice the average salary, etc.

If democracy also means accepting difference and allowing for criticism, then I cannot ever like the fact that Montenegro does not deserve to be called a democracy. Though historically always full of diversity, that fact was never given its proper due. This wealth of diversity was almost always, and this is especially true today, a fertile field for manipulation and conflict, often also for blood-soaked divisions. Criticism, that progress cannot do without ever since Kant, remains reserved in MNE only for narrow ineffective academic circles or else benign discussions at the bar, while any and all constructive criticism is seen as an attack against the state itself.

Media

I do not accept that a place where since 2004, when the editor in chief of Dani Duško Jovanović was killed, more than 80 attacks against reporters and media property have been registered, that such a place deserves to be called a state. Of those, 32 were reported in just the last two years. The targets of these attacks were by and large reporters at anti-government or pro-opposition media. In the most recent attack, Olivera Lakić, a reporter for Vijesti, was wounded and, like most such attacks, it remains unsolved, some never even see their day in court. When we add to this the dire financial situation of most media, as well as the unavoidable deep division into pro-government and pro-opposition media, as well as the inevitably high politicisation, then the media image is truly “pink”.

Continuous political meddling at RTCG (the public broadcaster) and the Agency for Electronic Media (AEM) was most directly demonstrated through the dismissal of members from the RTCG Board and its management. I am against the failure to establish editorial independence and professional standards at RTCG and that the RTCG Board remains unprotected against political influence and pressure, including in the appointment of its members. It is enough to take a look, and those with a dark sense of humour might even bring themselves to do so, at the programming of the public broadcaster. A universal approach and universality of content can be seen, but only if they’re part of a rare SF film.

Mafia and independence of the judiciary. Debt and debtors

I have much against the fact that dozens of young lives were ended before they properly began, in the “clash of the clans” (40 people were killed since 2015) and that the state is not showing its (lack of) power by seriously committing to fighting against organised crime. Many would say, how are they to fight against themselves.

I do not like the fact that the judiciary has become so degraded and has fallen so low that no attempt is made anymore to conceal political interference. As a reminder, I would like to refer to the arrest and detention of Nebojša Medojević, a Democratic Front (DF) member of parliament, as well as the fact that his colleague Milan Kneževeić served three months in prison for assaulting an officer, as well as other similar set-ups and the “Coup” trial that had been long in the works and whose only aim was apparently to do away with any opponents.

I do not like that we are breaking records when it comes to public debt. This year thanks to the loan for a highway segment whose construction is, of course, running behind schedule. The fact that the same highway is putting at risk one of the most beautiful and cleanest rivers in Europe, the Tara, that does not worry me at all, because as the responsible minister said, the construction of the highway did not move the riverbed, it just changed the river’s course.

The “envelope” scandal (a recording clearly showing a high state official (DPS) taking an envelope with 97000 euros from a businessman during the election campaign) has been suppressed, concealed and, I’m afraid, already forgotten. The expected parallel with the Austrian scenario: prosecution, resignations, dismissals, etc. remains just an expectation. The Anti-Corruption Agency refused to publish a decision against the ruling party (DPS) determining a breach of law and setting a penalty. I don’t know who wouldn’t be against such selective application of law.

Patriotism

I am against the fact that the official, and I’m afraid the only possible “patriotism” policy is precisely this misguided policy of “love for the state”. According to this policy, I can only help my country, my society, if I love it unconditionally. That is why any criticism, any possibility of change, progress, is viewed and perceived as hatred of the state, i.e. hatred of DPS or Milo. Because today it is “easier to imagine the end of Montenegro as a state than the end of DPS rule”.

Finally, perhaps I am most against the fact that these words will make me a traitor in the eyes of half of Montenegro, and a true patriot in the eyes of the other half, that in the by now historical game of rifts and divisions into patriots and traitors, I will be sucked into one of the two camps. I do not like that no third opinion, which is actually Other, i.e. different from both, can develop in such a post- or pre- democratic environment that is today’s beautiful Montenegro.

Radomir Radević

Croatia: “Đuro will forgive you beating you up”

We start this annual review of events that impact or are relevant for peacebuilding and dealing with the past in Croatia from the end, or from the end of summer in any case, given that this is unfortunately not the end, but only an overture indicating the fierceness campaigning for the presidential elections in Croatia that will take place late this year or in early 2020. The scapegoat is Milorad Pupovac, the long-representative of Croatian Serbs, and the ostensible motive is his interview to the Radio Sarajevo portal where, according to the Croatian Bishops’ Conference, the prime minister, various other ministers and veterans’ associations, he had “equated Croatia with NDH”. In actual fact, commenting on the wave of violence against those that identify or are perceived as Serbs, Pupovac said that such actions are “closely related to the historical revisionism manifest in Croatia in efforts to rehabilitate the Ustaša movement and establish it in the new European context, in the new European Croatia.” Those that he referred to as drivers of this process harnessed all their forces to show him how it was high time he left his homeland because, as a Serb, he had no right to speak that way about Croatia. Pupovac, however, was stating the obvious: according to the data of the Serb National Council, from 2013, when the wave of violence started with the smashing of dual language signs on state institutions in Vukovar, until 2018, there had been 1376 verbal and physical attacks on citizens of Serb nationality in Croatia, with 381 occurring only in 2018. The most recent case recorded this year took place in Uzdolje in northern Dalmatia where masked attackers assaulted a group of people, women and children among them, at a cafe where they were watching a football match of the Belgrade club Crvena Zvezda. Zvezda had been targeted a number of times this year, so, for example, a waiter doing seasonal work in Dubrovnik was beaten up for having a Zvezda tattoo and the Crvena Zvezda water polo team was assaulted while having coffee at the Split waterfront. This inspired creative interpretations of the Croatian reality to the effect that such incidents were proclaimed violence among sports fans. But the assailants of seasonal workers in Supetar on the island of Brač made sure we would have no doubts about what was truly at stake when they attacked four seasonal workers, among them two young men of Serb nationality from Vukovar, with cries of “who’s a Serb here, kill the Serb”. In June this year, Radoje Petković, president of the Serb National Minority Council in the town of Kastav, succumbed to injuries sustained a month earlier when he was brutally beaten by a war crimes suspect. The prime minister and the president go out of their way to relativise these events, calling them mere incidents and malicious provocations that should be resolutely opposed. How? The president demonstrated in a TV interview by energetically slamming the table with her fist. Already the next day, the front pages were adorned by photos showing a fan of the Hajduk football club from Split, wearing a mask, holding lit torches and donning a T-shirt that said “Kill the Serb”, being the hero on his side of the stadium. The police noted that “there were no major incidents” at the match.

What it’s like to be a Serb in Croatia

That the government has brought us up in its own image was best demonstrated by the campaigning for the European parliament elections, whose main actors and a litmus test for the state of society were again the Serbs. Because of their campaign “Do you know what it’s like to be a Serb in Croatia”, candidates Pupovac, Jović and the party they represent, SDSS, were accused of tendentiously launching or inspiring an unseen amount of violence in public space – throughout Croatia, their campaign posters featuring a mix of messages in Latin and Cyrillic script were regularly torn and/or vandalised with messages of hatred. This campaign elicited ambivalence from the great majority of Croats with no extremist leanings, and it was not rare to find comments on social media condemning the campaign as provocation, saying it was not reflective of the general state of society and that only a handful of extremists were defacing the posters. However, what remained unnoticed was the lack of any condemnation of such messages by both the parties in power and their opposition. When in the centre of Zagreb, across a campaign poster of SDSS for the EU elections featuring Milorad Pupovac, in the immediate vicinity of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, someone scrawls: “Slaughter Serb children. Kill the Serb” and similar acts are repeated in Split, Rijeka, Šibenik, Sisak and other places, this constitutes content that, in the words of the renowned lawyer Vesna Alaburić, can be legally qualified as nothing else than the crime of inciting genocide. It is thus qualified by the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide to which Croatia is a signatory. The commission of this crime does not require that genocide be committed, attempted, or likely, only that a message is expressed with genocidal intention, publicly, and that its content may reasonable be interpreted as direct incitement to destroy a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, in whole or in part. Legally speaking, it is entirely irrelevant whether the message will ultimately incite someone to action or not.

The campaign is no longer mentioned by anyone, but it is already evident that treating these acts as incidents, sporadic or unimportant is extremely dangerous for society as a whole.

Force, but not Violence

“Sometimes, a bit of force, but not violence, is needed when there’s a group of more than 50 people coming at you. There is no violence there, no bodily harm, shock bombs, tear gas, wire,” the Croatian president said commenting on statements by the BiH minister of security Dragan Mektić that there was evidence of violence by the Croatian police against migrants (as refugees on the Balkan route are now routinely referred to). That the Croatian police has resorted to illegitimate use of force in preventing these people from accessing European territory has been noted not just by the BiH authorities, but also by various non-governmental and humanitarian organisations whose reports have for months included evidence and testimony of police brutality and unlawful treatment. There are testimonies of beatings, confiscation of documents, money, food and water, denial of the right to seek asylum, unlawful transfer of people found in the territory of Croatia back to BiH, etc. Meanwhile, the EU acts as if this is none of its concern, so we must conclude that the use of illegitimate force against people of different skin colour on the periphery of the European continent is, in fact, desirable.

That such policies, which Croatia loyally upholds, are not just limited to the unfortunates from Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan or Iran was best illustrated by protests in Čakovec under the affirmative title “I want a normal life”, used to conceal their fundamentally racist content. The protests were directed at the Međimurje Roma population who, in the words of the organiser, “beat and steal”, who are “abusers under the influence of opiates,” “incapable of taking care of themselves, let alone so many children”. And should “therefore be taught how to live, how to raise children, how to manage their money and how to develop hygienic habits”. The racist rhetoric season with forged police statistics was meant to draw attention away from the systemic discrimination of Roma, attested by the fact that the Roma themselves were not allowed to organise a counter-protest, though such bans are unlawful and unconstitutional.

That is why among the social media commentators, the most quoted poem this year was “First they came…” changed to fit the moment: First they came for the Serbs, and I did not speak out, because I was not a Serb. Then they came for the Roma, and I did not speak out, because I was not a Roma… We still cannot be certain how to name the next social group in line for a lynching, given that it currently includes historians opposed to falsifications of history supported by the system and the government, especially from the period of 1941-1991, persons who speak out critically about the Homeland War and Tuđman’s legacy, reporters who report on hate crimes, in brief, all those whose speech and actions do not fit into the invented version of history, or the invented version of the state that has no place for them.

Who is it that’s leading us?

That we are falsifying history and discussing it in order not to ask too many questions about politics, crime in the public sector, corruption and other issues concerned with social ethics – this is abundantly clear. But apart from individual protests by courageous individuals and a few politicians, there is no organised resistance to such tendencies, neither in the opposition nor on the streets. There are many small fires and everyone is fighting the best they can and where they think they can truly make some headway – the left wing in the Zagreb city opposition against the unlawful manipulations of the mayor with city owned land, property, public space and projects; non-governmental organisations against the police and system managing the refugee crises; citizens’ initiatives and organisations against local authorities to protect their immediate natural environment, etc. Although the divisions within Croatian society are increasingly clear, and not just along ideological lines, solidarity has not yet become completely extinct, but after years of taking heavy blows, it is exhausted.

What ordinary citizens think about the reactionary tendencies in social development is hard to say beyond mere statistics. According to the German Federal Institute for Statistics, since Croatia’s accession to the EU, from 2015 to 2017, some 200,000 Croatian citizens have emigrated to Germany, of which almost 100,000 were employed. The number of Croatian citizens that have emigrated in the past two years is perhaps best reflected in the deserted villages and towns of Slavonia and Baranja. These citizens are predominantly ethnic Croats, and given that the villages of Lika, Banija and Kordun, where Croatian Serbs used to be the majority, have been empty since 1995, it is unclear who the Croatian right wing is so vehemently fighting. The emigration is far higher than the official statistics and the main trends are the following: “these are predominantly young people aged 20 to 40 who were usually employed and who usually emigrate with whole families. In contrast to previous emigrations, the majority of the current emigrants are young people with higher education degrees. Most respondents blame the current situation and mass emigration of young people from the country on incompetent politicians, the ineffective justice system and war profiteers. The immorality of political elites, legal uncertainty, nepotism and corruption are the prime motives that have contributed to emigration. Research has confirmed that political uncertainty and instability incited many to leave. Based on research results, we have seen that young Croatians are not leaving because of money, their aim is not to get rich. Wealth is not a key value to any of them. In Germany, they are prepared for more sacrifice and hardship than in their homeland, simply because they believe their efforts will pay off in Germany, while they have lost trust in their homeland”[1].

Davorka Turk

Kosovo: Rendering our stories

“Dede!“,

says this kid holding a gadget; “this school you said you had to walk to, 12.5 kilometers daily; google maps says it’s only 1.7 kilometers away…” The joke is circulating these days amongst youth in Kosovo, expressing their superiority toward the elders, for having the accurate information, here and now.

Neyse…,

allpoetry.com says that there is this poet who attended a Serbian Orthodox elementary school, studied Slavonic, Russian, Greek, Latin and French, and entered the Orthodox Seminary of St. John the Theologian… This is Millosh Gjergj Nikolla – Migjeni, for whom in wikipedia you will read that he is one of the most literate and most important literary writers of 20th-century Albanian literature, and a Kosovo portal would say that, no other poet of the Albanian nation has been so discreet in the realistic description of Albania’s social status.

But you know,

if you are an Albanian, and you are labeled “Esat Pashë“, that would mean you are the worst of the traitors. Well, not anymore; that was the narrative molded by the political opponents of his time. Otherwise, Esat Pasha Toptani (1863–1920) was an Ottoman army officer who served as the Albanian deputy in the Ottoman Parliament, cooperated with the Balkan League after the Balkan Wars and established the Republic of Central Albania, based in Durrës. Recently, a number of scholars from Albania are shedding light upon this interesting figure of the Albanian past.

Rendering our stories?

Yes! I am absolutely convinced that there is always the right moment to step back, recapitulate the past narratives and create an understanding of it that is useful for us today, in the here-and-now. The means will always change, but the time is always right. It is not about opposing the past narratives, it is about adding something better to them. For Kosovo society today, and for the whole region (they call us WB6 now; cool!) this has become of crucial importance for moving forward. And the only permissible movement in universe is indeed forward. Such a movement forward world make it possible for us to explore and learn more about those “Esat Pashas” from our pasts, to continue feeling the grief-stricken Migjeni’s poetry in Albanian by knowing of his Serbian heritage. And I dare to say, such a movement forward will enable us to understand why these 1.7 kilometers of today’s kid were dozens of kilometers for this Dede in the joke above. But it will not, under any conditions, give us the right to condemn that old man, nor those times gone by. There has to be something we still don’t know. And that’s exciting!

rather than a bio:

since May 2018, the author of this article got invited to be a member of the Preparatory Team for establishing Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Kosovo, initiated by the Office of the President of Kosovo. Such an initiative, like any other can be easily hijacked, having the current establishment, in Kosovo and all over the WB6. Maybe we need to learn how to add something better, not only to our pasts, but also to the here-and-now we get engaged in, or are affected by. We already live, and are conditioned by, a number of good and not-so-good undertakings from the past, and their aftermath. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Kosovo is yet another opportunity, still being shaped, to contribute to a meaningful transformation, in Kosovo, and wider.

and a post.scriptum

this article was thought as an analysis of the situation in Kosovo within Sep 2018 – Sep 2019 period; allow me just say that the “diplomatic tangos” continued in-and-around border issues, dialogue, 100% tariffs of Kosovo on Serbian products, and more. As for the past, a lot of energy was invested on finding ways to punish, blame, damage and win over “the other”. Laudly. Silent are only the voices of those less visible; on 14 March 2019, the UN‘s Special Rapporteur on Toxics said that “compensation should be paid to Kosovo Roma people who suffered lead poisoning while living for years in UN-run camps near a mining complex after the Kosovo war.” If this compensation is indeed paid, it would mean a lot to surviving Kosovo Roma population, and for the justice in Kosovo. If this statement is UN’s responsible overview of their own past, than better times are ahead of us.

Abdullah B. Ferizi

North Macedonia: Neither Here Nor There

“Life for All” in the North

After the consultative/failed referendum on the 30th of September 2018, and the long process of negotiations, amnesty and bribery, the Republic of Macedonia became the Republic of North Macedonia, and with it began its path towards joining NATO.

North Macedonia’s government coalition led by the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM) who ran the election campaign under the slogan “life for all”, the Democratic Union for Integration (DUI) and half of the newer Albanian party BESA, this past year made big progress in foreign relations but has been seriously failing to properly tackle most serious domestic issues that persist.

With the great burden of hope that a post-regime government governs, great disappointment may be the norm but it is not an overstatement to say that the new government has made too many mistakes, has lied too many times, given too many fake apologies and has failed to push forward needed reforms or has given up on some altogether, and disappointed most of the people who wanted or took action to bring about change. And this has frustrated so many people that the phrase “all are the same” has become a normal political phrase even among more politically aware citizens, lowering the seriousness of the crimes and injustice of the VMRO-DPMNE regime and bringing with it the risk of getting VMRO-DPMNE back to power. The same VMRO-DPMNE, unreformed and full of nationalists and criminals. All the while the other half, or a third of the named regime, DUI, are still in power, pretend to push the country towards its Euro Atlantic path yet use every chance to continue their corrupt practices and to keep the country ethnically divided.

In addition, NATO propaganda is normalizing the militarization of our society and is even penetrating schools to approach the youngest among us. At the same time, public officials, including the Prime Minister and the Spokesperson of the Government have contributed to normalizing hate speech although, after using it, have given superficial dishonest apologies.

One important positive event that happened was the Skopje Pride Parade, the first Pride Parade in the country. It was held on the 29th of June, with no serious incidents and with considerable, though superficial support by the government.

A Parent for the Nation

On the 21st of April 2019, we had the Presidential Elections, the first elections after the failed/consultative referendum on the change of the name. They represented a real challenge for SDSM who took on the risk of going ahead with the name change yet have been governing problematically, to say the least.

The elections, in a way, showed us the more probable and accurate result of the referendum if the opposition had not decided to boycott it, having in mind that the whole election campaign and the political discourse were focused and stuck on the name issue and the disappointment with the new government in most aspects. Especially in the second and final round, it practically divided the country much like it was divided during the referendum.

There were three candidates in the race to become the “parent” of the nation. Stevo Pendarovski from SDSM (who won), ran a campaign that struggled to push the messages across because it had to deal with all the shortcomings of the government. Another candidate was Gordana Siljanovska, a professor who, although wasn’t previously a member of VMRO-DPMNE, became their candidate and ran a nationalist campaign that was tragicomical and full of lies and irrational populism typical for VMRO-DPMNE but not typical for her personally. The third candidate was Blerim Reka, an Albanian professor who ran a refreshingly non-nationalistic campaign but struggled to be consistent when addressing the media, the Macedonians and the general public, and when addressing his Albanian supporters in his rallies.

It was ridiculous that all three candidates were insisting that they are not party candidates. Siljanovska, after being chosen to be VMRO-DPMNE’s candidate in their party congress, gathered signatures from citizens (VMRO members) to make the point that she is a non-party candidate. Pendarovski responded by doing the same and insisted he is an above-party consensual candidate although he was chosen by SDSM and the rest of the parties in government. Blerim Reka insisted he is an independent candidate although he was supported by two opposition Albanian nationalist parties and they actively assisted his campaign and got their voters to vote for him.

The election campaign was also problematic because of misogyny and very, very superficial feminism with patriarchal tendencies. Siljanovska’s feminism, especially with her campaign rhetoric, represented nothing but dishonest pandering, yet at the same time because of her sex and gender, as well as her age (she’s 64) Pendarovski’s and Reka’s supporters often made many sexist and misogynistic comments and attacks, which Pendarovski failed to condemn properly. And I think that because of Siljanovska’s terrible campaign and loss of the race, the political parties will be even more reserved in the future to go ahead with female candidates – they will justify it easier now and will use it as an excuse not to tackle their party patriarchal structures that greatly disadvantage women.

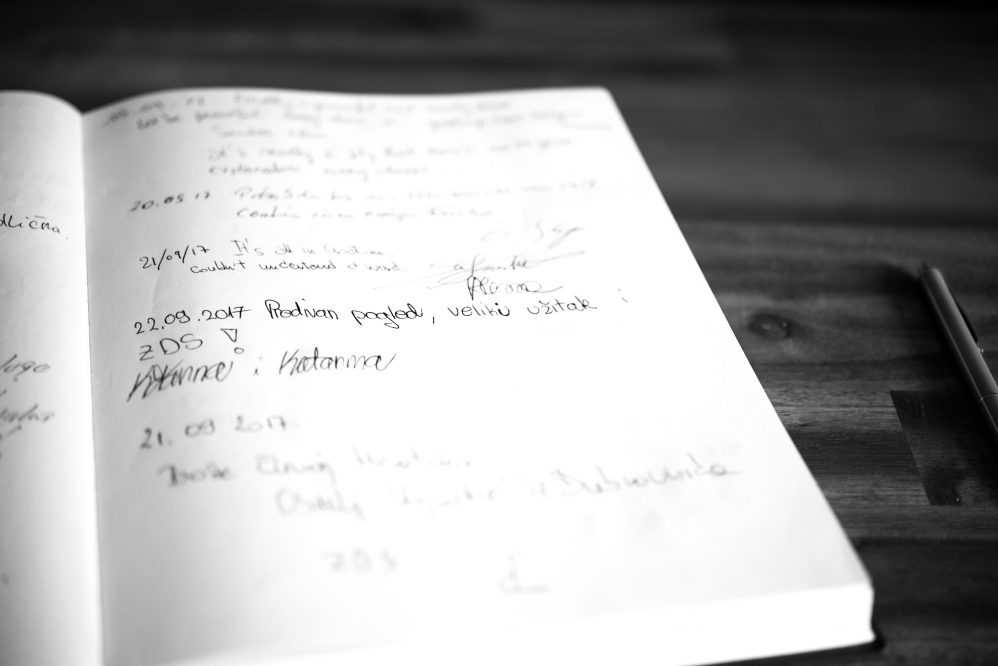

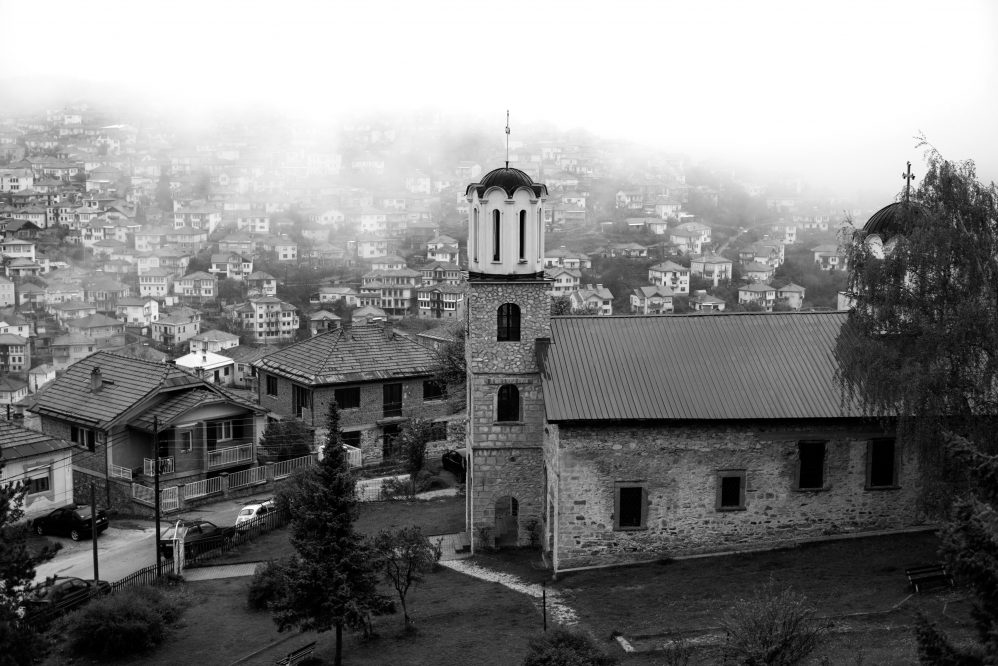

Sometime between the first and the second round of the elections, there was a nationalist incident in the fortress in Ohrid. Someone from an Albanian folklore group (not from the country) put up a huge Albanian flag on the fortress walls facing the city, and it caused quite a big nationalist and anti-nationalist backlash. He was arrested, fined and expelled from the country, but having in mind that during the Presidential elections Ohrid was having local elections too (the previous mayor died), this only favored VMRO-DPMNE’s candidate who later nevertheless lost. To add to this, although a bit off-topic, one of the main issues in the local elections (although it appeared on the presidential campaign too) was the building of an arguably illegal minaret of a mosque in Ohrid. There were even protests that tried hard to convince everyone that the issue is the (il)legality of the procedure and not the religion and ethnicity of those involved, but failed comically.

A Mixture of Extortion and Bribery

These past few months Macedonia has been quite shaken by an extortion/corruption scandal involving the Special Public Prosecution (which has been set up to handle all high-level crimes coming out of the illegal wiretapped recordings from the previous Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski and his cousin, the ex-Director of the Administration for Security and Counterintelligence, Sasho Mijalkov). After having begun working on over 150 cases with potential to become criminal charges, and quite a few criminal charges, the SPP got its reputation ruined by its chief, Katica Janeva.

The scandal broke out with the publication of a few videos and audio conversations by an Italian/Slovenian right-wing journalist on the website of the Italian newspaper La Verita. Allegedly, the two extortionists had promised the businessman Orce Kamchev – who is one of the richest people in the country, with very close ties to the previous government and a suspect in a few of the criminal cases opened by the SPP – that he would walk free or at least get a much lighter sentence than he should for the crimes of criminal association, fraud, money laundering and other related crimes. The two had promised that they can deliver that because of their close ties to SPP’s chief, Katica Janeva.

Janeva, after taking a borderline illegal medical leave and disappearing from the public for some time, of course denied being involved and said that one of the extortionists had been misusing her name. But she is (allegedly) heard in one of the audio conversations, confirming that what has been discussed with the extortionist will indeed be done; that “everything will be okay”.

This investigation is being run by the regular Public Persecution, after Kamchev approached the Prime Minister Zoran Zaev who went ahead and reported it to the Public Persecution. Although, obviously, that didn’t stop the opposition to ask for a resignation from Zaev and ask for new elections, as well as accuse him of being the one that has ordered the extortion. The specific reasons why Kamchev chose to approach the Prime Minister and not the Public Prosecution (as he is legally obliged to) are unclear, but it seems as though he wanted to incriminate him too. Especially having in mind that the video recordings in his house got in the hands of the right-wing anti-EU journalist Laris Gaiser who is in the presidency of the Paneuropean union along with Gruevski’s former adviser Andrej Lepavcov.

Not to go into too many other details, as a result of the investigation so far, quite a few persecutors from the SPP, as well as a few people from SDSM with close ties with one of the extortionists, have given statements to the Public Persecution sharing what they know and the two extortionists and Katica Janeva are under arrest. No one else from SPP and no one from SDSM has been charged so far.

In any case, this scandal paralyzed the Special Public Persecution, and it sort of seems like an organized effort to dismantle it and bring down all the high-level investigations and charges brought forward. As a result, the only institution with the credibility and the obligation to seek and bring justice for the crimes of the VMRO-DPMNE regime’s officials and their rich friends not only got its reputation ruined but is also under threat to have its investigations taken over by the regular Public Persecution which is not really reformed after having served the regime for over 11 years. And it leaves the public further disillusioned and divided.

Whether Katica Janeva has fallen prey to greed or she was naïve enough to be set up, or whether Orce Kamchev was extorted or he tried to bribe people to avoid facing justice for his crimes (both equally and non-exclusively possible), while Katica is under arrest and SPP is slowly being dismantled, Orce Kamchev is free and living the rich life.

Love Thy Partner

In last year’s report I wrote that SDSM and DUI are continuing the tradition of VMRO-DPMNE and DUI in “DUIng business” in accordance to the law, but with serious suspicion of corruption. Now I can confidently say that indeed it continued, involving other coalition partners. DUI took it a step further and its party officials are blatantly breaking the laws and not facing the consequences.

The country has a serious problem with corruption for decades – it’s not something new. But with the new government, there was new hope that finally, at least the corrupted ones, in the previous 11 years will face justice and that we’d move forward in tackling the issue. Needless to say, that did not end up being the case. It began relatively soon after they came to power, especially clearly when the Fund for Innovations gave big grants to companies to innovate, among which were the companies of the Vice Prime Minister, millionaire Kocho Angjushev. After the scandal broke out, instead of resigning from the government, he got his companies to pull back and give up the grants. The public prosecution opened a criminal inquiry into it, but to this day to the best of my knowledge there are no information regarding the findings of that inquiry.

DUI party officials have had produced multiple scandals this past year. One of corruption and theft scandals was initiated by the Ministry of Social Affairs which found out that the pension fund is missing a couple million euros; that the money planned for the second pension fund has disappeared. The Directors of the institution responsible for it, have been appointed from DUI for years, and this shook the coalition relations a bit and again somehow disappeared from the public – no news, no information, no criminal charges.

Other criminal affairs include DUI officials building illegal objects, physically attacking people, contracting their own firms for public works, abusing their positions, buying а luxury car for municipality’s (mayor’s) needs after the central government payed back most of the huge municipality debt … The “owner” of the named car, DUI mayor of Struga, Ramiz Merko, justified it by arguing that it is shameful for the mayor to be driven in a car that is not good enough. There are plenty of other examples, albeit not only for DUI.

On a side-note, it’s important to mention that these cases show another grim reality of the Macedonian politics and interethnic relations: the general public, and Macedonian nationalists especially, see the political opportunism and breaking of laws by the DUI officials as an Albanian approach to politics and as Albanian nationalism, yet fail to see that this behavior is primarily harmful to the Albanians outside DUI’s political structures. That it is those Albanians that have been left with no state protection and borderline bullying and violence in DUI hands. To illustrate with an example, the two men physically attacked by the DUI member of Ohrid’s city council Nafi Useini, are both Albanian.

The SDSM mayor of the majority Roma municipality Suto Orizare, Kurto Dudush, who is also Roma, recently had an audio recording leaked to the internet where he is heard insulting and beating up someone. There is an ongoing investigation but it seems that this case too will disappear like those related to DUI. This to note that the Roma citizens have also been left to deal alone with their local bullies while Macedonian nationalists justify the bullying as a cultural thing rather than a state structural problem and neglect.

And all this is tolerated by the SDSM officials partly because they are also focused on their interests and corruption, partly because it could worsen coalition relations and partnerships, and partly because the non-Macedonian ethnic issues are seen, by the bigger Macedonian parties, as issues to be left to those ethnicities themselves. Regardless of what that means for those communities.

In any case, the Republic of North Macedonia with its endless naïve hope, continues its path towards the EU; the everyday issues of the citizens will just have to wait for now.

Emrah Rexhepi

Serbia: Who’s Next?

For months now, the first thing I ask myself when I open my eyes in the morning is: “How will I get to work?” I rent a flat in Belgrade, in the city centre, and the Centre for Nonviolent Action also has its offices in the city centre. What’s the problem? The problem is that Belgrade, as a city with a population of more than two million, has a large city centre and it’s not easy to get from one end to the other. In the past few months it’s been neither quick nor easy. Every route through the inner-city centre is closed, changed, displaced. Belgrade looks like a large construction site where an ambitious investor with suspicious 1990s funds had started work on a castle, only for the hand of justice or underground competition to catch up to him, leaving the works forever unfinished and a legacy of bequeathed megalomaniacal wishes and enormous debt. Two plaster lions guard the gates of the castle. Such are the aesthetics of Belgrade. Megalomaniacal, kitsch, a cheap looking expensive investment. And then, when I manage to make my way, usually on foot, to Republic Square, whose renovation works have shut down the most visited part of Belgrade for a year now – this would be akin to shutting down the Moscow Red Square for a year or Trafalgar Square in London – on the dug-up concrete of the construction site, I find no one. Sometimes, in a corner somewhere I might spot two or three workers smoking or the like. Mostly, nothing is happening. That nothing is paid for by the city budget, to the tune of close to 8 million euros (922 million dinars). Public transport is in shambles. I got on a bus yesterday, it had air conditioning and enough seats. I thought, finally, something works in a country where everything is falling apart, perhaps there is still hope, one shouldn’t be cynical. Two stops later and the bus stalled. It broke down, all the passengers had to continue on foot. So much for hope.

Why am I starting this text for the wider public with seemingly insignificant details of my morning worries? I have been writing or reading texts like this one for years, and each year, the situation in Serbia gets worse in every segment of society. It is difficult to explain in a relatively brief text everything that is worse compared to last year, the list is very long, and the human brain has the fortunate tendency to delete bad things from memory. But then when I start recalling everything that has happened, I come up against an avalanche of fascism, curtailed freedom, pressure, blackmail, murder, corruption, lies, people being targeted and calls for lynching, violence against people who think or speak differently, discrimination on all grounds, poverty, unemployment, brain drain, mass emigration of qualified people hungry for work of all levels of education… It occurs to me, if I start from the personal, from what we all have in common, and explain how it’s different in Serbia than elsewhere, perhaps this will serve to illustrate my point? Perhaps it will then be easier to understand the problems we face and the things we have to live with daily.

The Tank

We live in an atmosphere of fear, tension, accusations of treason, being called second-rate Serbians (them, the nationalists are first-rate, we are “second-rate”, the “others”, those who are not part of the “we”, degenerates, rejects), and any common sense question posed to anyone in power or in the ruling party (though there is no difference between the two, here the ruling party has all the power, there are no institutions, no controls, everything is subjugated to a single party and a single man) is considered as an attempt to destabilise the state and engagement in hostile activities.

In late August, before a match with the Swiss BSC Young Boys, a tank was installed in front of the largest (for now, though the president has promised to build a new, grandiose, “national”) stadium in the country, popularly known as “Marakana”, home to FC Crvena Zvezda, A tank from Vukovar. Whether that very tank was in Vukovar, no one can say with certainty, but it is symbolic of the 1990s wars and the destruction of Vukovar, which was referred to by the Serb side in those years and by nationalists today as the “liberation of Vukovar”. A war symbol in front of a football stadium is not there to send any other message than a threat. Already the next day, a tractor was installed in front of FC Dinamo’s stadium in Zagreb – to symbolise Operation Storm, the ethnic cleansing of Serbs from Croatia, who escaped to Serbia on tractors. The police minister stated that it was “not a tank, but a model of a tank” and that he could “not understand why anyone would see a model of a tank in front of the stadium as a symbol of the nineties”.

He went on: “This was obviously meant to serve as a political game for some sort of attack, primarily on President Aleksandar Vučić, because apparently he is now to blame for this because he is to blame for everything that happens. This is obviously a case of politicking by part of the opposition that, unfortunately, has nothing better to show for itself.”

Vučić is to be credited for everything happening in the country, and everything that goes wrong is an attempt to set him up. Everything revolves around his life and work as he oversteps his constitutional authority in every segment, he is both prosecutor and police, and prime minister, and minister, and an independent body, he is responsible for everything and he solves everything. In political terms this is called a dictatorship, but in Serbia there is no force that would call it by its proper name and stand up to it.

What the police minister calls the “politicking by part of the opposition” is actually the division of the opposition into “good” and “bad” opposition to the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS). The good opposition, ideologically aligned, are Vojislav Šešelj, a convicted war criminal and now president of a parliamentary party and a member of parliament, and his Serb Radical Party, the origin of Aleksandar Vučić and the major share of SNS that left it in 2008 to form their own party. Members of their former party are the “good” opposition. The other part, the “bad” opposition, is everyone else on the political scene: from the extreme right-wing Boško Obradović (Dveri), then Vuk Jeremić (People’s Party) and the centrists in the Democratic Party and the Movement of Free Citizens, all the way to the left-wing civic movements of Ne davimo Beograd and Local Front. That opposition is broken down and weak for two reasons: the first is that they are satanised by the ruling structures headed by Aleksandar Vučić who never misses an opportunity, no matter how banal and beside the point, to disparage those parties and their leaders, while they themselves are at the same time completely prevented from appearing on national television and in the major newspapers. The other reason is that the opposition (with the exception of the Local Front and Ne davimo Beograd) is mostly made up of people from the previous government who are responsible for losing the elections and ushering us into a period of rule of poorly disguised radicals that will last for who knows how long.

Given that regular parliamentary elections await Serbia already in 2020 (I will emphasise that they are regular, because previous parliamentary elections were held in 2012, 2014 and 2016), it is not clear how any change in government will be possible given the present electoral conditions and disarray in the administration. And even if such a thing were to happen, there is still the possibility of a “natural coalition” between SNS and SRS to replace the current cooperation with SPS, a party that has been a loyal coalition partner.

Hope

Although, viewed from a distance, elections may look like an opportunity for change like my bus from the beginning of this text, with the current distribution of power among just a few people, change is not even a hope. Perhaps a dream.

Hope had appeared in late 2018 when, first in Belgrade and then throughout Serbia, citizens came out in protest against the brutal beating of opposition politician Borko Stefanović by hooligans close to the government. “Stop the bloody shirts” was the initial call of the protestors, which had the inclusive potential to gather around it everyone who was opposed to violence, whatever their political affiliation. Though initially unorganised, without a clear vision or goal, these protests kept gathering more and more people each Saturday at 6 pm. One of the most imposing gatherings was on 16 January 2019, on the day Oliver Ivanović, a politician from Kosovo, was killed, with suspicions that individuals close to the government in Serbia were behind the murder and that the authorities were harbouring two suspects: Zvonko Veselinović and Milan Radoičić. Led by the Local Front, a citizens’ association from Kraljevo, who set out on foot on 12 January towards Belgrade and travelled 170 kilometres, the resounding silent question of the citizens was: “Who killed Ivanović?”

The very next day, Vučić organised his own gathering – making use of a state visit by Russian President Vladimir Putin and all the state privileges, honours and institutions, the welcome was actually the beginning of the “Future of Serbia” campaign whose megalomaniacal gatherings, expensive videos and state privileges are used by the ruling party to present its vision of Serbia – once upon a time. It was never clear why the campaign was run in the winter and spring, unless it was a response to opposition gatherings. The government hired buses to transport its actual and coerced sympathisers (coerced and blackmailed on account of their jobs: Serbia has a law prohibiting further employment in state institutions, which means that since 2014 until today, no one could acquire full-time employment, and part-time employees are easy to manipulate, threaten and blackmail) from town to town, with expensive backdrops and populist speeches, while on the other side, in many towns, people opposing this government gathered every Friday or Saturday. Voluntarily, in show, in the winter, without a sound system and most often – spontaneously.

In the spring, after the opposition attempted to enter the Serbian Radio and Television building, in protest that the public broadcaster was nor reporting on their activities, and after the gathering on 13 April where citizens from other parts of the country were invited, this type of protest slowly started decreasing in intensity. People still gather every Saturday evening in Belgrade and Kragujevac.

The Target

The problem of lack of media freedoms is perhaps the most worrying: it prevents citizens who do not have access to online information or the only non-Vučić cable TV station – N1 from finding out whether the police minister bought a fake diploma both for his BA and his doctoral studies, whether an SNS official and director of Koridori Srbije highway company was speeding and hit a car waiting at the toll booth, which resulted in the death of the young woman in that car, only to vanish from the scene, who, how and with whose money organises people to defend (provide support and legal aid) to the mayor of Brus who sent his secretary 15,000 (no, there’s been no mistake or extra zero – 15,000) text messages amounting to sexual harassment, who installed the tank in front of the stadium and why, but more importantly: who will remove it, who is building mini hydropower plants and destroying Serbia’s rivers, why have almost all the trees in downtown Belgrade been cut down, and when will this city start functioning normally… If you ask any of these questions out loud, you will be labelled an enemy of the state. A second-rate Serbian. Self-hating. We all wear targets on our foreheads, all of us who write about these things even on our private social media profiles. And we all receive threats from the SNS bot team made up of public sector employees who spend their working hours hounding the opposition to this government or writing up its glorious successes. (By definition, a bot is a robot imitating human behaviour. Vučić has turned that game upside-down, too – he has made people into robots. And robots, even these paid human ones, lack the minimum of feelings and empathy, so they draw targets, aim, threaten…)

Let me remind you that Oliver Ivanović talked about being a target in the 2017 text on the Kosovo Context. By the time our report was printed, Ivanović had already been murdered. Since we know nothing about the circumstances of his murder or who ordered it, we can only ask: who’s next?

Katarina Milićević

[1]The above are findings of the research study “Contemporary Emigration of Croats to Germany: Characteristics and Motives”; Migration and Ethnic Issues, Vol. 33, No. 3, 2017. The study is available HERE.